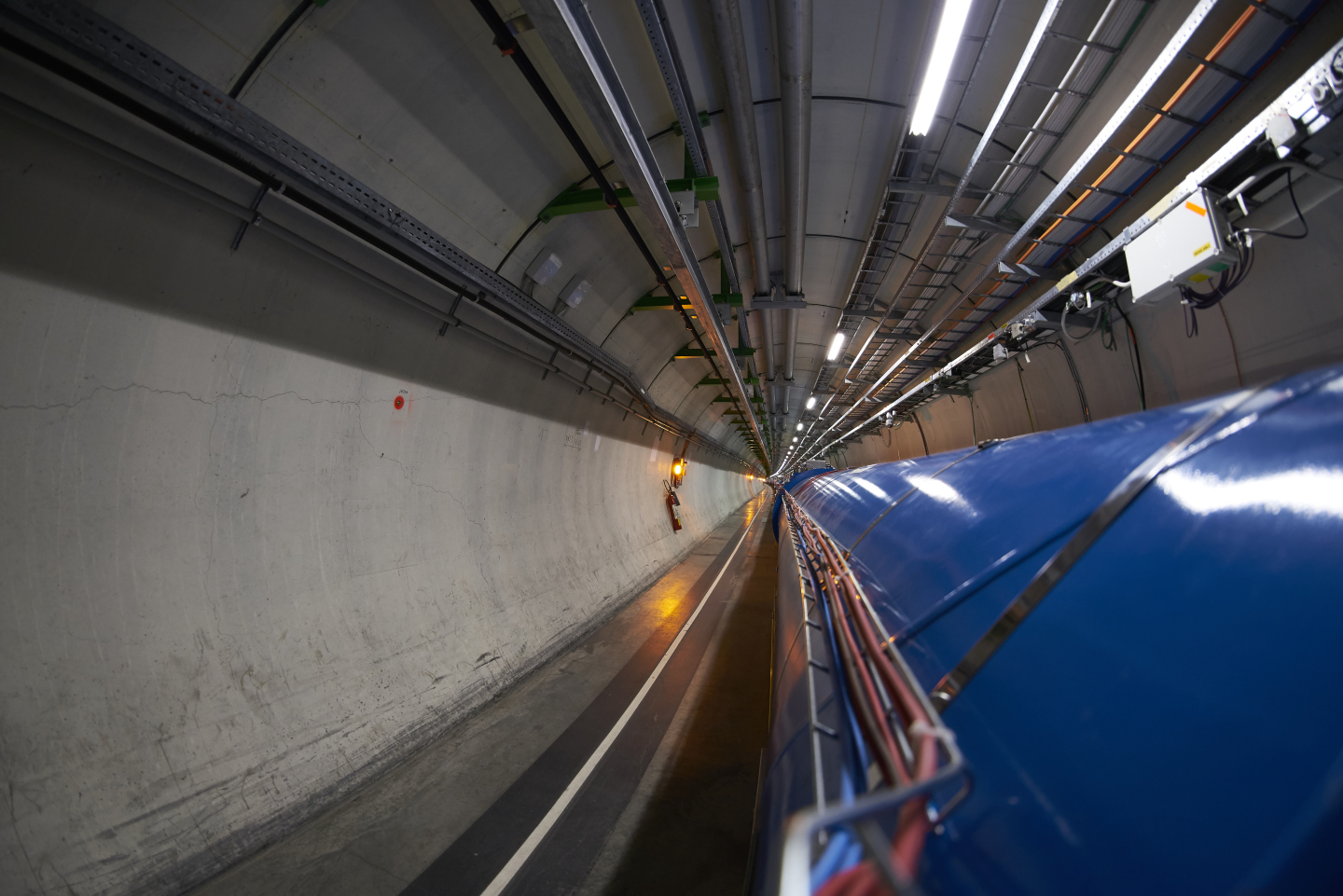

Today, the LHC once again began circulating beams of protons, for the first time this year. This follows a 17-week-long extended technical stop.

Over the past month, after the completion of the maintenance work that began in December 2016, each of the machines in the accelerator chain have, in turn, been switched on and checked until this weekend when the LHC, the final machine in the chain, could be restarted by the Operations team.

“It’s like an orchestra, everything has to be timed and working very nicely together. Once each of the parts is working properly, that’s when the beam goes in, in phases from one machine to the next all the way up to the LHC,” explains Rende Steerenberg, who leads the operations group responsible for the whole accelerator complex, including the LHC.

Each year, the machines shut down over the winter break to enable technicians and engineers to perform essential repairs and upgrades, but this year the stop was scheduled to run longer, allowing more complex work to take place. This year included the replacement of a superconducting magnet in the LHC, the installation of a new beam dump in the Super Proton Synchrotron and a massive cable removal campaign.

Among other things, these upgrades will allow the collider to reach a higher integrated luminosity – the higher the luminosity, the more data the experiments can gather to allow them to observe rare processes.

“Our aim for 2017 is to reach an integrated luminosity of 45 fb-1 [they reached 40 fb-1 last year] and preferably go beyond. The big challenge is that, while you can increase luminosity in different ways – you can put more bunches in the machine, you can increase the intensity per bunch and you can also increase the density of the beam – the main factor is actually the amount of time you stay in stable beams,” explains Steerenberg.

In 2016, the machine was able to run with stable beams – beams from which the researchers can collect data – for around 49 per cent of the time, compared to just 35 per cent the previous year. The challenge the team faces this year is to maintain this or (preferably) increase it further.

The team will also be using the 2017 run to test new optics settings – which provide the potential for even higher luminosity and more collisions.

“We’re changing how we squeeze the beam to its small size in the experiments, initially to the same value as last year, but with the possibility to go to even smaller sizes later, which means we can push the limits of the machine further. With the new SPS beam dump and the improvements to the LHC injector kickers, we can inject more particles per bunch and more bunches, hence more collisions,” he concludes.

For the first few weeks only, a few bunches of particles will be circulating in the LHC to debug and validate the machine. Bunches will gradually increase over the coming weeks until there are enough particles in the machine to begin collisions and to start collecting physics data.